The Perishable Past

The Shigir Idol and the Limitations of Knowledge

Some 12,500 years ago, a wooden giant towered over the open grasslands and sparse forests of the Ural Mountains. Set amid stunted, hardy stands of larch and pine, the five-meter-tall giant stared out through sightless eyes, taking in the landscape, its wildlife, and its few human inhabitants. A while later - years, decades, or centuries - the giant fell, slipping into the swampy, waterlogged ground. A peat bog formed over it, layer after layer of sodden organic material, protecting the delicate wood from the ravages of time and the elements. There the giant stayed, out of sight and unknown, until 1894. Miners digging through the peat in search of gold stumbled on this unique artifact of a forgotten age.

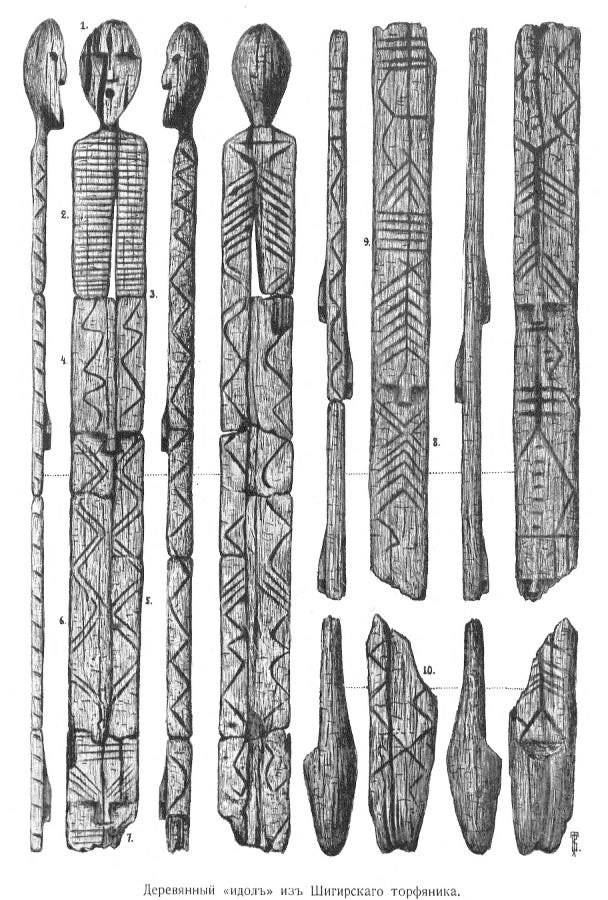

The giant is known as the Shigir Idol, and there is nothing like it in the world:

The carefully carved, three-dimensional face at the top of the sculpture is not a friendly one.

Seven other faces line the body of the sculpture, three on the front and four on the back, all of them unique. The faces are scattered among a profusion of zig-zagging lines and shapes running the length of the statue.

What, exactly, is this thing? Who made it, and why?

“Who made it” is the easiest to answer: a group of wandering foragers, hunter-gatherers who made their home in the vicinity of the Ural Mountains in the cold, uncertain days of the Younger Dryas climatic period. They hunted elk and boar, coexisting with wolves and bear in this harsh landscape of open tundra and forest patches, gathering whatever plant foods were available to sustain them.

As to what it is and who made it, we don’t have any real idea. The closest analogue is something like a totem pole, but whatever meanings the object conveyed are completely lost to us. Perhaps it marked a boundary between two groups’ territory. Maybe it watched over an important place where the dead were exposed to the elements or cremated. It might have been an offering to ancestral spirits or a token of thanksgiving to the supernatural forces embedded in the landscape. Those are just blind guesses drawn from more recent ethnographic parallels. Anybody who says they know for sure is either supremely overconfident or lying.

The Shigir Idol is a one-of-a-kind object. There are a few other scattered items of art from the Urals around this time, mostly figures carved into elk antler, but nothing like the enormous, brooding statue. That’s not because it was unique in its time and place, but because it’s the only one that' has survived to the present.

Organic items, not just enormous wooden statues carved with haunting faces, are very difficult to find in the archaeological record. Wood rots, textiles decay, soft tissue decomposes, and bone dissolves. Sometimes, we get lucky, and very occasionally conditions bless us with an abundance of organic materials. Waterlogged sites, peat bogs, glaciers, and arid deserts can all work miracles of preservation, keeping safe rare or unique objects that would otherwise be lost to the record.

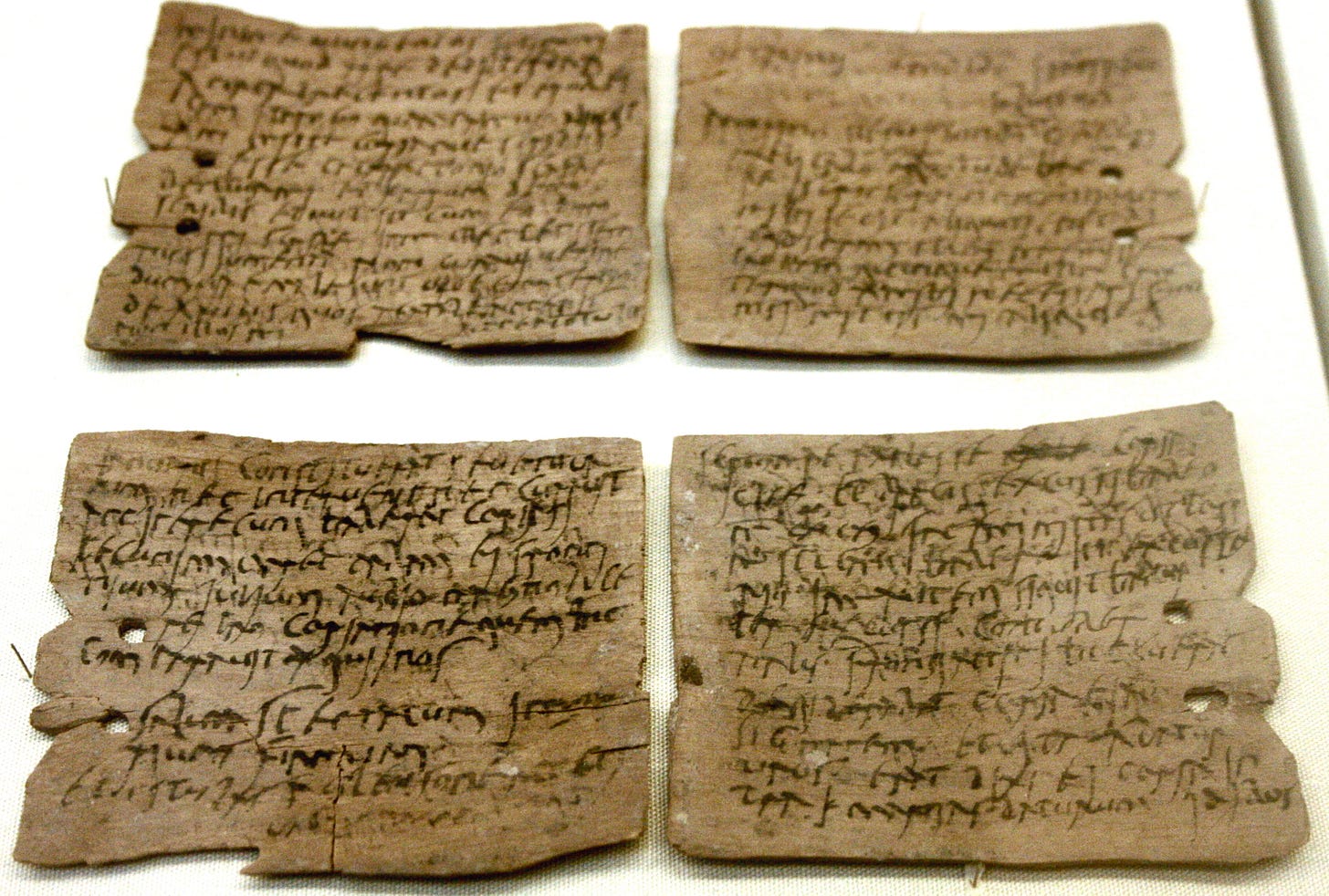

These are a few of the Vindolanda Tablets, thin-sliced pieces of wood covered in cursive Latin writing and dating to the late 1st or early 2nd century AD, found in waterlogged conditions at a fort along Hadrian’s Wall:

They’re incredible documents, detailing daily life at one of the Roman Empire’s frontier outposts. The wife of the commander of a nearby fort, named Claudia Severa, invites another woman, Sulpicia Lepidina, to a birthday party and adds a postscript in her own hand. An officer writes asking for more beer to be sent to the fort. These are precisely the kinds of things that make up the fabric of human existence, yet we practically never find them. They simply don’t last.

When we are lucky enough to find a site like Vindolanda, where researchers have recovered everything from shoes to combs to boxing gloves, it reveals how much of the past is simply lost to us due to the nature of what tends to stick around. Stone tools, sure; pottery sherds; often, metal objects; sometimes, human remains. We practically never find hide or textile clothing, any kind of wooden item, or woven baskets. Human remains quickly decompose; even if carefully buried, acidic soil conditions might eat away even the durable bone. Only rarely does soft tissue, skin, or hair survive.

What preserves in the ground makes up only a tiny fraction of the material world in which people lived, thrived, and died. Because of this, our access to their world will always be extremely limited.

Consider our old friend Ötzi the Iceman, the naturally mummified body of a man killed more than 5,000 years ago, high in the Alps. If not for the remarkable preservation conditions, we might have a few scraps of bone and a couple of stone tools; instead, we have a bow and arrows, a birch-bark container for holding the embers of a fire, the contents of Ötzi’s stomach, the charcoal in his lungs, and even the arrowhead embedded in his shoulder. Ötzi is a complete person, an individual, fully realized and three-dimensional.

Despite Ötzi’s dramatic death, and the final journey that led to it, the man himself and his material possessions are less remarkable for their inherent qualities than the fact that they’ve survived. People like Ötzi, places like Vindolanda, and objects like the Shigir Idol are a tease, a momentary glimpse through the veil of time at the stunning material texture of lost times and places.

Ötzi, for example, was practically covered in tattoos: 61 of them, in 19 distinct groups spread over his body.

He wasn’t the only ancient person with tattoos; his contemporary, the Egyptian Predynastic mummy Gebelein Man, had a Barbary sheep and a wild bull tattooed on his shoulder.

We have every reason to think tattooing is incredibly common in global and historical perspective. The ethnographic record is packed with societies that practiced some form of body modification, including scarification and various forms of tattooing, yet our evidence for the practice in the past is minuscule. The archaeologist Aaron Deter-Wolf, one of the world’s experts on ancient tattooing and whom I interviewed on today’s episode of Tides of History, told me that the tattoos found on Ötzi and the Gebelein mummies are the earliest in the record. Yet older tools that were probably used for tattooing have been found, dating back millennia before even Ötzi and Gebelein Man. There’s no reason to think the practice couldn’t have gone back much further into the distant past.

But how could we know? The evidence is simply gone.

It’s something we must constantly bear in mind when thinking about the past. Our picture is inherently incomplete, our access limited. That doesn’t mean the task of understanding the past is hopeless, but embracing the limits of what we know is essential to doing the job right.

It’s not a bad lesson to bear in mind for the present day, either.

I wrote a book! It's called The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance, and Forty Years that Shook the World. The book comes out in July, but you can pre-order the e-book or hardcopy here. I’d really appreciate it if you did!

Thank you for another fascinating read. I never knew about the Shigir Idol.

You're very good at interpreting societies with limited written records. How about something on the Phoenicians (Carthage) and whether or not Tophets were child sacrifice.

I am shocked by articles I came across and also fascinated / disgusted that elites might sacrifice their own children to maintain their status and standing (my interpretation of what the elites might have been doing) to appease the gods.

If true, no wonder the Romans hated them!