When we think of the ancient world - I mean really ancient, not the Greeks and Romans of classical antiquity - the first civilizations that come to mind are those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. Egypt had the pyramids and mummies, after all, while Mesopotamia was defined by its sophisticated, literate, and highly urbanized society. Pharaohs like Khufu and Rameses II and kings like Sargon and Hammurabi have managed to retain some name value even after thirty or forty centuries, which is no mean feat.

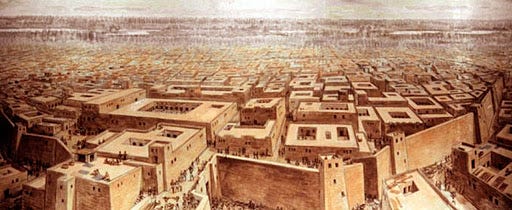

Yet if we were to fly over that particular stretch of the world around 4,000 years ago, our eyes might instead wander east, toward South Asia. Instead of pyramids and ziggurats, we would see large cities of mud-brick, dozens of smaller urban centers, and hundreds of villages. These settlements dotted the shore of the Arabian Sea from the present-day border of Iran and Pakistan to Gujarat in western India. The banks of the Indus River and its tributaries, swollen with the monsoon rains, were thick with people and mud-brick buildings from the sea to the fringes of the Himalayas. This was the Indus Valley Civilization. Though less known today, it was a society every bit as populous and sophisticated as those of Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Cities with populations in the tens of thousands, complex traditions of craftsmanship, dense trade networks, stunning skill in hydraulic engineering, and even a written script defined the world of the Indus Valley Civilization. In reality, it stretched far beyond the environs of its namesake waterway, from near Delhi in the northeast to Gujarat in the south and Balochistan in the southwest. Throughout that huge territory, many times the size of the pharaohs’ domains or the fractious city-states of Mesopotamia and containing at least as many people (if not substantially more), a remarkable uniformity of life took hold between around 2600 BC and 1900 BC.

Without readable written texts - the distinctive written script remains unfortunately undeciphered - our knowledge of the Indus Valley Civilization rests on archaeology. The material remains of this world are distinctive and sometimes stunning, in their own specific way: not in the form of massive stone-built monuments to the glories of deceased kings or the palaces of an exclusive nobility, but instead vast expanses of millions of baked mud-bricks piled up into city walls, houses, elevated platforms, and even public baths.

Four or perhaps five major cities dominated the region: Dholavira in Gujarat; Mohenjo-daro on the lower Indus; Rakhigarhi near present-day Delhi; the still-unexcavated Ganweriwala in what is now the Cholistan desert; and Harappa in Punjab, which gives the civilization its alternative name of “Harappan.” Each of these cities, which might contain tens of thousands of inhabitants, served as a regional center for smaller cities, towns, and villages in the surrounding area. Food and raw materials flowed into the urban center, while finished goods flowed out, connecting each city to both the smaller settlements and the other huge cities of the Indus Valley world.

This was a complex world. Goods, even food, traveled over long distances: People at Harappa, 500 miles from the coast, routinely ate dried or salted fish caught in the Arabian Sea and transported upriver. Craft specialization reached a high level, with toolmakers, copper-smelters, gem-cutters, builders, and other craftsmen producing goods of exceptional quality. High-quality, mass-produced pottery was fired, decorated, and distributed over large areas. We take that kind of trade and connectedness for granted today, but it wasn’t the norm in the ancient world, even in Egypt and Mesopotamia. The Indus Valley Civilization had its regional variations, but it was far more uniform, over a far larger area, than its contemporaries.

That uniformity expressed itself in several ways. The cities were all built to rigid, pre-planned grid patterns, with broad public streets intersected by smaller lanes at right angles. The same system of weights and measures was used throughout the Indus Valley world and even beyond, making it easy to compare quantities of goods for exchange. The same architectural styles, and even the same proportions for each mud individual mud-brick (4:2:1), appear throughout the region. The mysterious script, with its impressed seals, was likewise uniform.

What we don’t see in the Indus Valley Civilization is evidence of strong hierarchies. As far as we can tell, no kings, exclusive cliques of nobles, or other elites dominated Indus society. There are no grand royal tombs or palaces, no monuments to the power and ego of a powerful figure determined to make his or her mark on the built landscape. Cities were filled with large complexes of relatively uniform houses, with rooms for domestic and craft activities arranged around a central courtyard. These houses were then grouped into separate quarters or neighborhoods. No one individual or group seems to have stood above the rest. For that matter, there’s precious little evidence to suggest that even the great cities somehow exercised power or sway over their smaller neighbors.

This doesn’t mean that everybody was totally equal within Indus society; instead, it means that we don’t yet have the evidence or the conceptual tools to understand how Indus society was organized. It was certainly comprised of different groups, who presumably cooperated and competed with one another, but we don’t really have any idea on what basis those groups were organized: maybe kinship, maybe occupation, maybe ethnic identity or religious affiliation.

We simply don’t know. What we can say is that the people of the Indus world found ways to work together on a staggering scale. They built an extraordinary hydraulic infrastructure to guarantee their access to water in an arid region while simultaneously keeping themselves safe from the potential dangers of the monsoon and annual flooding. They built enormous public buildings, including baths, platforms, temples, and others whose function we can’t yet discern. Their civilization lasted for 700 years in its mature form, and even longer if we include the prior phase (“The Age of Regionalization” in specialists’ terms), which went back another 700 years before that.

When the Indus Valley Civilization did finally come to an end, after around 1900 BC, its great cities were abandoned. Its descendants stopped using their distinctive script and their system of weights and measures. Why? As with all complex questions, the answer almost certainly revolves around many causes and their interaction rather than a single simple factor. The main cause was probably rooted in climatic shifts. The Indus Valley Civilization had come into existence in the first place in a time of increasing aridity, and eventually its hydraulic wonders could no longer make up for the decreasing rainfall and lack of water, particularly outside the Indus proper. Its people took up different ways of life. Others migrated east and south, into the Ganges Plain. In that way, the Indus Civilization’s legacy lived on for thousands of years to come.

If you’d like to learn more about the Indus Valley Civilization, check out today’s episode of my podcast, Tides of History.

I wrote a book! It's called The Verge: Reformation, Renaissance, and Forty Years that Shook the World. The book comes out in July, but you can pre-order it here.

This likely isn't a useful thought exercise, but I'm trying to figure out *why* a civilization this big/successful/important isn't considered like Egypt and Mesopotamia? My amateur first thought is that Napoleon's invasion of Egypt, plus the overt, visible nature of the pyramids, etc. really pushed it to the forefront of European imagination? Which makes me assume, perhaps incorrectly, that the British, Portuguese, and others didn't care or investigate the archaeology of the Indus valley to the same degree? Too busy pillaging the region, I suppose.