Neolithic China

The Dawn of Agriculture and Social Complexity

I don’t know about you, but I’m a big-time rice enjoyer. Put it on a burrito, mix it up with some coconut curry, eat it as a side with your bone-dry grilled chicken when you’re on a diet. It works for pretty much everything.

Rice is the most valuable agricultural commodity on the planet. Hundreds of millions of metric tons of it are produced every year, an amount valued at more than $300 billion every year. Billions of people around the world rely on it as a staple of their diets, and have done so for millennia all over East, Southeast, and South Asia, and beyond.

But the rice that’s so popular today has a distinct beginning as a cultivated crop, a beginning that arrived somewhere along the Yangzi River more than 10,000 years ago. (The rice traditionally grown in West Africa, and which was brought across the Atlantic by enslaved people and merchants in the early modern period, stems from a separate domestication event. It’s not as productive as its Asian cousin, and so is less widely cultivated now.)

Ten millennia in the past, rice grew a bit beyond its current range thanks to slightly warmer and wetter climatic conditions at the dawn of the Holocene. The people living around the Yangzi River, and slightly to the north of there, were quite happy to use the stands of wild rice growing in their homeland. Grasses might not seem like the most natural food source for people to exploit, because it requires a great deal of processing (grinding, cooking, etc.) to make it edible. As part of a forager’s diet, however, it offered advantages: It was plentiful, it was reliable when other food sources like wild game came up short, and if properly stored, it could last for years.

Around the Yellow River, northern China’s key waterway, rice didn’t grow. Millet, however, grew in abundant quantities. As their counterparts had done further to the south with rice, the inhabitants of northern China learned to process it. A couple of thousand years of experimentation led from simply collecting wild grasses wherever they were found to planting wild varieties in gardens and fields, then intentionally and unintentionally selecting for traits to make those grasses more productive and less likely to fall off the stalk. Farmers created their crops, the ancestors of the foods we eat today, and the increasing viability of the crops created farming as a way of life.

For a variety of reasons, successful farmers tend to have large numbers of children, who expand outward from their core areas, taking their way of life with them. This process of demic diffusion defines most centers of early agricultural innovation around the world. Farming begets more farmers, who tend to spread out. For this reason, Neolithic China - an environment home to not one but two distinct agricultural traditions - produced a stunning diversity of early farming cultures. Starting around 7000 years ago, after 5000 BC, these farming cultures exploded in numbers, scale, and complexity. They filled up new territories and built more and larger villages. Towns followed, and leaders in the form of chieftains and kings. Social hierarchies and inequality defined these new Neolithic societies, distinctions of rank that could be inherited across generations.

These were the foundations on which organized states, writing, and what we might eventually call “Chinese civilization” built, many thousands of years down the road.

But long before that, there were simply clusters of distinct Neolithic cultures. Each probably spoke its own language, almost certainly belonging to different families. Some lived in villages formed of neat, orderly rows of semi-subterranean houses, like the Xinglongwa culture in the arid hills of northeastern China, eating deer, acorns, and millet; others lived in stilt-houses perched over swampy river landscapes. At the Kuahuqiao site near the mouth of the Yangzi (dating to 5000 BC), which has incredible preservation thanks to its waterlogged conditions, we know the inhabitants ate a staggering variety of foods: dolphin, water buffalo, tiger, turtle, fish, and rice. We also know that the inhabitants spent a lot of time out on the water, using canoes like this one:

There were similarities between these cultures, however, and these Neolithic cultures interacted with one another over space and time. All of them turned to plant foods as a major part of their diet, processing them with stone grinding tools:

![Stone Quern and Roller, Peiligang Culture (c. 6100-5000 BC), unearthed at Peiligang, Xinzheng, Henan Province, 1978. It is exhibited in the section of Life and Production in Neolithic China, an exhibition of Ancient China in the National Museum of China. [Photo by Xu Lin / China.org.cn] Stone Quern and Roller, Peiligang Culture (c. 6100-5000 BC), unearthed at Peiligang, Xinzheng, Henan Province, 1978. It is exhibited in the section of Life and Production in Neolithic China, an exhibition of Ancient China in the National Museum of China. [Photo by Xu Lin / China.org.cn]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!9G5Q!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fde9e2a54-eff7-4b17-bd12-395cc5172b60_900x506.jpeg)

Starting in the northeast, jade became an important luxury good, worked by specialized craftspeople and associated with high-status burials. It eventually became common across much of China:

Slowly but surely, as populations rose, villages got bigger, and more settlements appeared, these Neolithic societies started to show more of what scholars call “social complexity.” There are a few different aspects to this. One is craft specialization: Making jade objects, for example, requires a ton of skill, time, and specialized tools. Time spent doing that craft and learning the necessary skills for it is time not spent working in the millet fields, feeding the pigs, collecting acorns, or hunting deer. The same holds true for shaping and firing fine pottery, making oceangoing canoes, or grinding high-quality stone axes. They’re not things an amateur rolls out of bed to do in the morning, and that means somebody else has to provide them with the necessities of daily life. That’s one aspect of social complexity.

Another is “settlement hierarchy.” If some settlements within a region are bigger than others, have larger and fancier buildings, or fulfill different purposes, that’s evidence of social complexity.

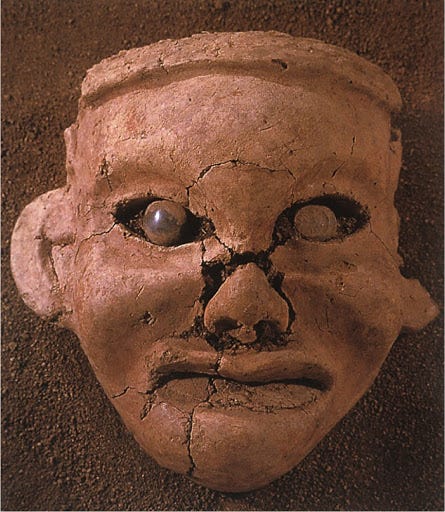

The site of Niuheliang belongs to the Hongshan culture in northeastern China, lasting from about 5000 BC to 3500 BC. It’s actually a cluster of sixteen sites spread over 50 square kilometers, at the very center of which is a structure known as the Goddess Temple. There are no settlements anywhere near Niuheliang; it was purely for ritual or religious purposes, whatever that meant to the Hongshan people.

That’s social complexity in a nutshell: craft specialization and settlement hierarchy, along with a shared sense of religious belief or spirituality, though we’ll never know precisely what that was for the Hongshan people who came to Niuheliang.

Social complexity could take different forms elsewhere, though. The village of Jiangzhai belongs to what’s known as the Yangshao culture along the Yellow River. It’s contemporary with Niuheliang, but the people here had much different ideas about how to organize their lives. Here’s a model of Jiangzhai:

You can see the clusters of houses around a relatively open central area, with a ditch outside the houses. On the other side of the ditch was a cluster of burials, a cemetery, corresponding to the house-cluster on the inside of the ditch. Jiangzhai was divided up into what were probably kin-groups, and within those kin-groups, some people were leaders. We don’t see much in the way of social hierarchy at Jiangzhai, but at later Yangshao sites, some burials were much richer than others, with jade artifacts buried even in children’s graves.

And there were still other ways of living, too. This is a stilt-house of the Hemudu culture, roughly contemporary with Jiangzhai and Niuheliang (c. 5000-4000 BC), located near the mouth of the Yangzi. The people who lived in it fished in the river and the ocean, worked in irrigated rice paddies, and collected wild plants for food. They must have been good at it, because Hemudu sites explode in number, which speaks to rapid population growth.

The Hemudu people used canoes like the one from Kuahuqiao, and probably took them far away from the Yangzi. Sites with artifacts like those of the Hemudu people show up along the southern Chinese coast as far as the Pearl River delta, where Hong Kong is located today, and Taiwan. The other Neolithic cultures were on the move, too: the Yangshao people up the Yellow River, groups along the middle Yangzi south toward southern China and eventually Southeast Asia, and so on. Most of the languages spoken in East and Southeast Asia, and many spread out to even more distant locales, belong to families that likely expanded from homelands in present-day China during the Neolithic.

This was an incredible and diverse efflorescence, and it didn’t stop there. In millennia to come, the settlements got bigger and acquired fortified walls and palaces. The grave-goods got richer - more and larger pieces of jade, finer pottery - and so did the people buried in them, sometimes with human sacrifices to accompany them into death. Before too much longer, the first states would appear, with people wielding genuine power over their lessers. The first stirrings of recorded Chinese history were almost in view.

If you thought this was cool, check out today’s episode of Tides of History.

Check out perennial grain production for the first time in the 10,000 years of human agriculture at https://landinstitute.org/our-work/perennial-crops/ According to their literature I recently received from them through the work of their partners in China, perennial rice production has jumping from zero a decade ago to millions of acres ten years later. They say switching from annuals to perennials is repairing agriculture's 'original sin', to use biblical metaphor.

Hey Patrick, Happy new year. Love your pod and appreciate these posts. I was especially struck by what you said in this episode about the non-inevitability of gender hierarchy (go Jomon!). Related issues in an opinion piece in today's NYTimes, link here: https://nyti.ms/3rM2OTl