Migration and the Expansion of Farming

How Did Agriculture Leave the Fertile Crescent?

Up until about 12,000 years ago, nobody on the planet subsisted by intentionally cultivating crops or keeping domesticated animals. Everybody was a forager, using some combination of hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plants to get enough to eat. But first in the Fertile Crescent around 10,000 BC, then independently and later in East Asia, two different spots in the Americas, New Guinea, and several places in Africa, small groups of people began to farm. Because agriculture provided food for far greater numbers of people, it led to towns and cities, craft specialization, and eventually the development of states and what we think of as “civilization.”

This was a long, slow series of processes. Nobody woke up one day and decided to adopt the full suite of agricultural behaviors, including sedentary life, cultivating permanent fields, keeping herds of sheep or cattle, and all the institutional and mental adjustments to a much different way of life. Instead, this “Neolithic Package” emerged in pieces. There were sedentary communities, genuine villages, before anybody ever cultivated crops. Mobile bands could easily cultivate some fields if they wanted. The domestication of the most important animal species almost certainly happened in a different place than the beginnings of growing the cereal grains, like wheat. It took a long period of cultivation for domesticated plants to take on the distinct characteristics that separate them from their wild relatives, like larger and non-shattering grains.

All of this took a couple of thousand years of cultural experimentation to figure out. When it did come together as the full package, the result was the first expansion of farming techniques outside the Fertile Crescent of Israel, Jordan, Syria, southern Turkey, Iraq, and Iran. Unambiguously agricultural sites start to show up east, on the Iranian Plateau, then further into Central Asia, and eventually at places like Merhgarh, in eastern Pakistan, by about 7,000 BC (or 9,000 years before present). It took about 3,000 years, then, for farming to get from its homeland to the fringes of South Asia.

To the west, farming sites show up on the island of Cyprus and in central and southern Anatolia. The early settlement of Çatalhöyük is in southern Turkey held hundreds of people, packed into a dense collection of white houses that butted up against each other:

The inhabitants of Çatalhöyük walked around on the settlement’s rooftops and climbed down into houses with ovens. The skulls of bulls were a common decoration, and presumably had some sort of ritual meaning or role in a household cult:

So who were the people who made Çatalhöyük their home? Where had they come from? Were they the descendants of local hunter-gatherers who adopted the farming way of life, or were their ancestors migrants from further east in the Fertile Crescent?

Farming wasn’t necessarily a pleasant way of life when compared to foraging. Early farmers were shorter than their hunter-gatherer cousins, had worse teeth thanks to a high-carbohydrate diet of grains, suffered from more repetitive-stress injuries, died younger, and were generally less healthy. But even though more of them died, farmers were able to have significantly more children and then use their labor to perform agricultural tasks. The result, despite greater rates of early death, was population growth.

Growing numbers led to migrations. The farmers who spread to Çatalhöyük, Cyprus, and then further west to the Aegean were the descendants of the hunter-gatherers who had first adopted farming in the northern reaches of the Fertile Crescent. In scholarly terms, the westward movement of farming was a demic expansion, a movement of people rather than ideas.

Farmers showed up on the Aegean island of Crete and the coastlines of present-day Greece and Turkey in the centuries after 7,000 BC, around the same time they showed up in Pakistan. Genetic evidence shows that these early Aegean farmers were the descendants of the Anatolian hunter-gatherers, migrants who had hopped along the coastline of southern Turkey or come through the mountains further north. With a couple of tenuous and possible exceptions, they weren’t locals who decided to abandon their old way of life and become farmers.

The story of farming’s movement further north and west into Europe is likewise almost entirely one of demic expansion outward from the Aegean. After a pause there that lasted for several hundred years, over the course of just a few generations farmers multiplied in numbers again and settled the northern Balkans and the Danube River corridor from Hungary to the Black Sea. From the fringes of this region, which became the densely populated heartland of Neolithic Europe, migrants would push further into central and northern Europe.

At the same time, farming migrants had began moving west along the northern edge of the Mediterranean. They showed up first in Sicily and southern Italy, then hopped into central Italy by boat before reaching southern France, the Iberian coast, and even into the Atlantic.

We know they went by boat because of a remarkable archaeological site in central Italy called La Marmotta. It was representative of this migrant culture, known as the Cardial thanks to its distinctive pottery. About 5700 BC, the rising waters of Lake Bracciano covered the village. The waters of the lake preserved organic materials, particularly wood, of the kind that almost never survive for more than 7,000 years. One of the things archaeologists found at this site was a series of big dugout canoes, a couple of them more than 30 feet in length:

A team of archaeologists sailed a replica across the open Mediterranean all the way from Sicily to the Atlantic coast of Portugal. Some scholars think they might have been fitted with an outrigger, or lashed together in a pair to form a catamaran; if so, they would’ve been even more seaworthy.

Using boats like this, the coastal migrants traveled dozens or hundreds of miles at a jump, and made it all the way to Portugal by 5500 BC. It took a while before they started moving inland, mostly using the major river valleys like that of the Rhone in France or the Ebro in Spain.

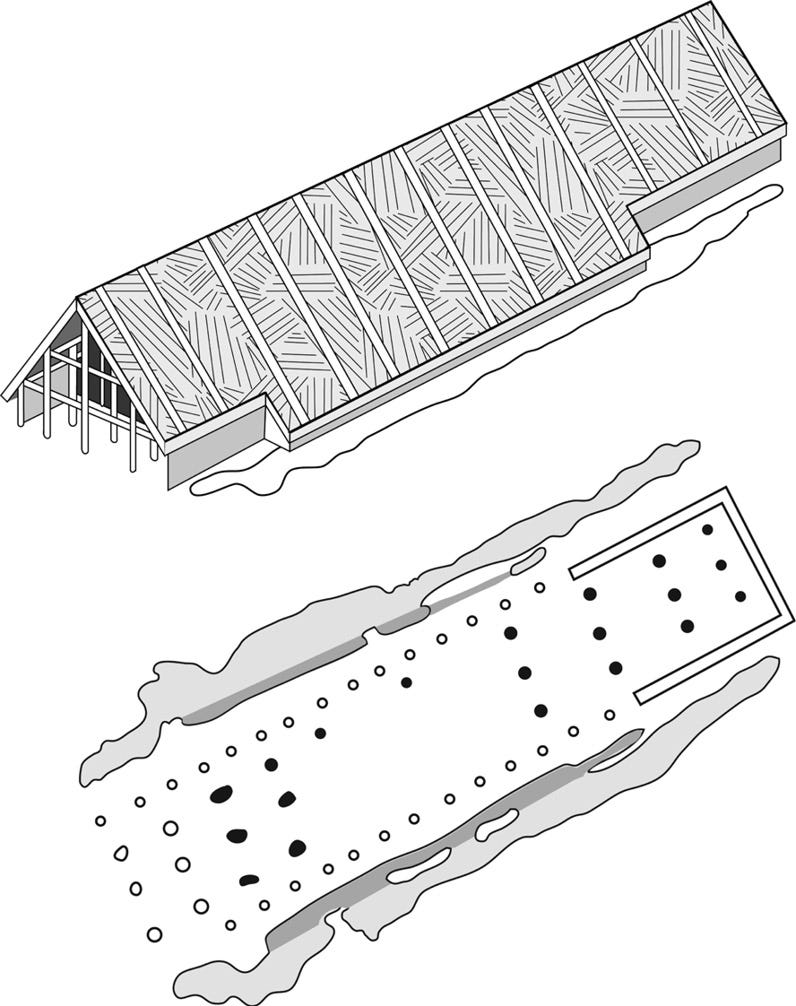

Around that same time, 5500 BC, a frontier group living in eastern Hungary and western Austria developed a new way of life. Where most of their compatriots in the greater Danube area lived in orderly settlements, with many small rectangular or square houses grouped together, the people of the Linear Pottery Culture (Linearbandkeramik in German, LBK for short) started living in enormous timber longhouses:

Here’s a present-day reconstruction built on the island of Jersey:

We don’t know why they did this, but it has to speak to some sort of underlying social change: maybe extended families or clans became more important, maybe there were new ideas about leadership or hierarchy, but it’s hard to say. What’s clear is that these folks started to spread out from their core region, and did so quickly.

The people of the LBK were looking for very specific environments: islands of fertile loess soil, a wind-blown post-glacial sediment, with the right temperatures and amount of precipitation. The LBK folks were Neolithic Goldilocks when it came to choosing a pace to live. It couldn’t be too hot, too cold, too wet, or too dry. Otherwise, their preferred crops - emmer and einkorn wheat, grown in small, intensively cultivated fields - wouldn’t grow the way they wanted. These were the only places they built their distinctive longhouses, which eventually clustered in unplanned, somewhat chaotic settlements as the population grew. New groups were constantly splitting off to settle new islands of loess, eventually showing up everywhere from northern France to the Black Sea coast of the Ukraine in just a few hundred years.

The LBK culture was shockingly homogeneous, given its extent, and extremely conservative. They built the same kinds of houses, used the same kind of pottery, grew the same crops, and kept the same domestic animals, passing along their cultural package to their descendants, who then migrated and took it elsewhere. The LBK people barely seem to have interacted with the hunter-gatherers who were still present in their own preferred spots across Europe. Here’s some LBK pottery:

Eventually, however, the LBK came to an abrupt end.

Around 5000 BC or shortly after, we can start to see evidence for violent conflict in LBK sites. There were massacres, like the one at Schöneck-Kilianstädten near Frankfurt in Germany, where at least 21 people were killed and thrown into a mass grave. A couple seem to have been shot with arrows. There’s unambiguous evidence of either torture or post-mortem mutilation, namely smashing the victims’ legs. For the most part, they seem to have been bludgeoned to death:

Several other sites like this are known, like Tallheim and Schletz-Asparn near Vienna. Here’s the mass grave at Tallheim:

For some reason - maybe population pressure, unstable social hierarchies, or environmental degradation - LBK society essentially tore itself apart. We have no real idea why, but the effects were clear. The ubiquitous longhouses disappeared over large stretches of its former range. Populations dropped. It would be centuries before all the former regions were reoccupied, and their new occupants weren’t all descended from their LBK predecessors. Their Mediterranean cousins had been more successful, the tortoise to the LBK hare. Much more slowly, they pushed north from the coasts and river valleys, eventually reaching northern France shortly before the LBK culture collapsed. Where the two long-separated cousins met, and later melded with the remaining hunter-gatherers of Europe, a new era followed. That one produced the incredible earth and stone monuments that still stand today. That’s what I’ll cover next time.

If you’d like to learn more about this, today’s episode of Tides of History, my podcast, covers the first farmers of Europe in greater detail; this is one of a bunch that will cover the Neolithic, as this phase is known, in global context.

If you’ve enjoyed this, please subscribe and share:

Further Reading:

Stephen Shennan, The First Farmers of Europe: An Evolutionary Perspective

Chris Fowler, Daniela Hoffman, and Jan Harding (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe

Alasdair Whittle, The Times of their Lives: Hunting History in the Archaeology of Neolithic Europe

Hi Patrick, this is my first time visiting your substack site, but I have been a listener to your podcast since the Rome days. I enjoyed Roman and Early Modern series. I was a very wary of your announcement to move the current Neolithic time frame. However your manner of communication have warmed me up to the topic over the last few months and introduced me to a whole new world. Keep up the good work.

I notice you write (essentially) "Even though agriculture involved poorer nutrition etc., people were able to have more children more rapidly." That implies a difference in fertility rates specifically. A) am I understanding that right, and b) is there any speculation or evidence that agricultural packages supported higher fertility? Like maybe the nutrition, even if it was bad in some ways, was good at supporting more frequent pregnancies. Maybe the type of work allowed more frequent pregnancies, or new cultural practices forced it. Maybe it's that more children survived to adulthood for some reason, even if that adulthood was stressful and precarious.

I am LOVING the prehistory series. It's all just totally new to me. I'm glad you're talking about social structures and state or pre-state structures whenever you're able, because I'm trying to get through Fukuyama's "The Origin of Political Order" and so far it's really light on history ... I deeply want some facts to either buttress or challenge what I'm reading. I also want him to define his terms better. The practice you've had structuring narrative makes your work much more accessible and credible.