Where did we come from, and how did we get here?

There are a lot of different ways to answer that question. “We” is a matter of definition; so is “here.” For the next year on my history podcast, Tides of History, I’ll be taking the broadest possible approach to both of those terms, covering the deep history of humanity from our earliest origins as a distinct lineage. When and how did we separate from our closest ape relatives? When did anatomically modern humans first appear? How are we related to the other species of archaic humans who occupied the planet until the very recent past? How did we spread out across the planet? What drove us over the next horizon, to try out the next innovation, to survive and thrive? When and where did we start growing crops, building cities, trading goods, forging metals, and creating states?

Thanks to brand-new scientific research and cutting-edge archaeology, this is a great time to take a look at these questions and try to come to a better understanding of the long, twisted, and fascinating human past. In the first episode (and first post below) we go from our earliest ancestors at the point of divergence from the common ancestors we share with chimpanzees all the way to the emergence of anatomically modern humans some 300,000 years ago. It’s a long, strange, and confusing journey, less about direct descent than a diverse tapestry of features and populations at any given time.

What’s really striking about these long-lost people, whom we know only through their bones and the stone tools they left behind, is how human they seem, how much like us. Follow along to meet some of our ancestors, with a few stray thoughts and comments about our ancient friends.

You can listen to the episode here, or subscribe on Apple Podcasts or your player of choice.

(All images via Wikimedia Commons)

Jebel Irhoud 1: 300,000 years before present, the oldest anatomically modern human, found at the cave of Jebel Irhoud in Morocco. There’s a wonderful reconstruction of this individual by the Kennis brothers, but I couldn’t find a picture of it labeled for re-use. The upshot, if you believe their reconstruction, makes him look quite familiar; you wouldn’t look twice if you saw this guy in modern clothes on the street. He really does look like a perfectly modern person, and he lived at a time when there were Neanderthals, Homo heidelbergensis, Denisovans, late-surviving Homo erectus, and probably multiple other species of humans still roaming the planet. Our earliest ancestors weren’t alone.

Sahelanthropus tchadensis: 6-7 million years before present; reconstruction from fossil “Toumai”, by John Gurche. We have no idea whether this lone fossil represents our direct ancestor, but it lived at roughly the right time and has some of the traits we’d expect from a species around or just after the divergence between the ancestors of humans and chimpanzees.

Australopithecus afarensis: 3.2 million years before present. This species is comparatively well known from a large number of remains. Their mixture of archaic and seemingly modern traits, particularly the gait (which we know from preserved footprints! incredible) makes them a solid candidate for a population in our direct line of ancestry. Afarensis is just one representative of a broad and diverse lineage that maybe, probably, eventually gave rise to the genus Homo. Another, quite different, group of australopthicene descendants eventually became the genus Paranthropus, which looks bigger, more robust, and more ape-like than the hominins more closely related to us.

The famous “Lucy”: Australopithecus afarensis, 3.2 million years before present.

Homo habilis, or rudolfensis: I find Homo habilis deeply confusing, as do specialists in the field. There’s no real consensus as to the dates, features, or even the existence of the species. It might have appeared as early as 2.8 million years ago, or perhaps more like 2.1 million years ago, or maybe it simply overlapped with late australopithicenes, creatures like Lucy. There’s likewise no consensus as to whether habilis belongs in the direct line of human ancestry or was rather an ultimately unrelated offshoot.

INTERLUDE: Making Oldowan tools: 2.6 million-1.7 millions before present. Used by Homo habilis (?) and late australopithicenes.

Homo erectus, or georgicus. 1.8 million years before present, found at Dmanisi in Georgia. These - the earliest identifiable hominin remains found outside Africa - form an interesting collection of remains, all of them dated to within a few tens of thousands of years from one another at a single site. Despite the chronological clustering, the remains vary a great deal among themselves in morphology (facial structure, teeth, size, etc.). Specialists debate as to whether they even represent the same species: Perhaps there were several that occupied Dmanisi in a relative blink of an eye, or maybe the species itself was quite diverse. The latter seems more likely to me.

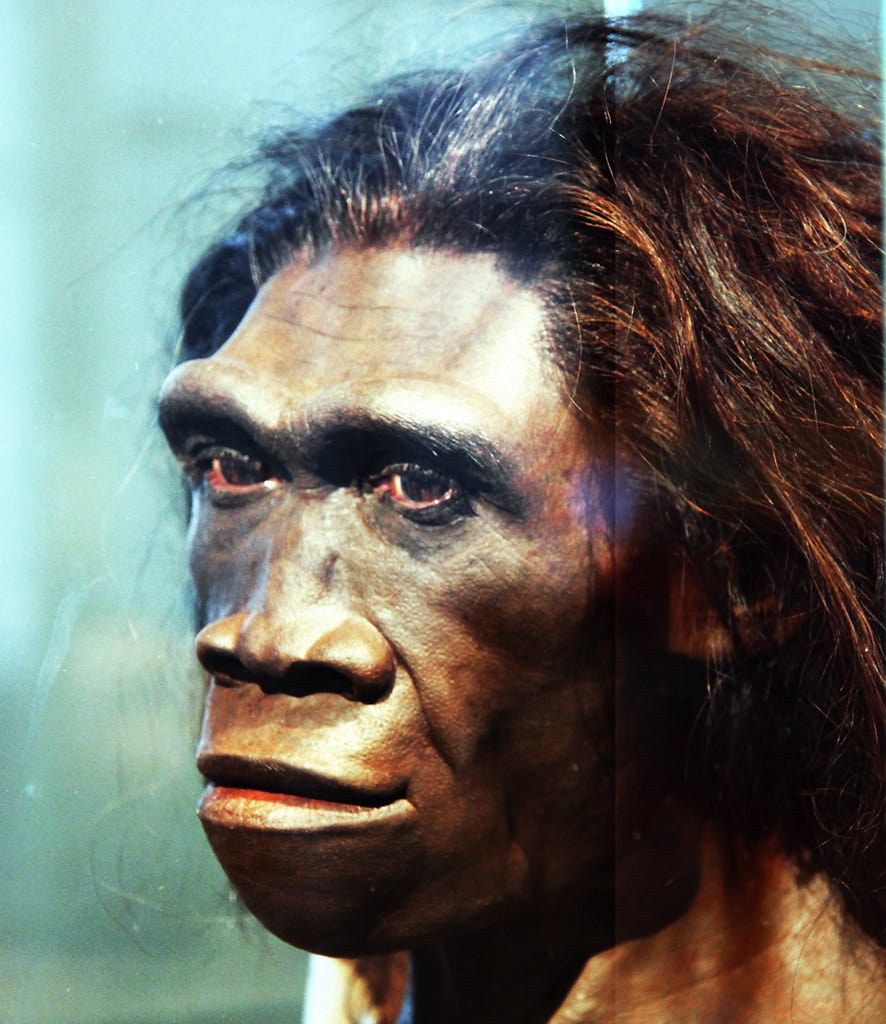

Homo erectus: 1.7-600,000 years before present, with some likely later survivals. First reconstruction by John Gurche, second reconstruction by the Kennis brothers. Erectus was the most successful and widely dispersed species of human prior to us, Homo sapiens. Homo erectus remains have been found everywhere from Indonesia and China to Africa and Europe over a very long period of time. They represent the probable direct ancestors of us, Neanderthals, Denisovans, and all the other later-surviving human species.

INTERLUDE: Making an Acheulean hand-axe (1.76 million-130,000 years before present)

Homo antecessor: 800,000 years before present. If the cut marks on Homo antecessor remains from Atapuerca in Spain are anything to go by, they seem to have enjoyed some light cannibalism. Until recently it was thought that antecessor was a good candidate for a direct ancestor of modern humans, but a recent paper using dental proteins as evidence has argued that they’re instead a less-related offshoot.

Homo heidelbergensis: reconstruction by John Gurche, based on the Kabwe skull, 300,000 years before present; total range 700,000-300,000 before present. Likely the last common ancestor species, or a species that contributed to the gene pools, of both anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals, our nearest cousins. They’re found in both Europe and Africa; Homo rhodesiensis is sometimes considered a distinct African species, but it’s more common to group rhodesiensis as a subtype of heidelbergensis more broadly. They were a big, robust, and well-adapted species, with large brains and a propensity for big-game hunting.

Heidelbergensis was a clever species. This is one of the Schöningen spears, dated to between 380,000 and 400,000 years old, and it was almost certainly made by Homo Heidelbergensis. This is a lethal wooden throwing and hunting spear - it’s weighted in the middle, as one would a modern javelin. A skilled javelin-thrower succeeded in tossing a modern reproduction of one of the Schöningen spears a shocking 70 meters, some 230 feet. That’s wild. The evidence isn’t conclusive, but it’s also possible that they even tipped some of their spears with stone projectile points. If this is true, they would be the first known composite tools in human history.

In the next post, and next episode, I’ll be talking about the other late-surviving species of archaic humans: Neanderthals, Denisovans, and the ghost populations whose fossils we’ve never yet found.

Selected Sources and Resources:

Alice Roberts, Evolution: The Human Story (2nd edition). DK, 2018.

Ian Tattersall, The World from Beginnings to 4000 BCE. Oxford, 2008.

John Hawks’ Weblog. An amazingly detailed and accessible look at various aspects of paleoanthropology.

Check out the incredible reconstructions of the Kennis brothers and John Gurche.

I'm loving this move. I remember reading Clan of the Cave Bears as a teen and starting to research prehistory and finding it so difficult. This is great and I am really loving the photos. It is a great visual representation of the theme of moving apart and coming together over and over again.

Hi Patrick, another fan here, from the Netherlands this time. You have singlehandedly rekindled my long time slumbering love for history and I am so very grateful for that.

(Side note: thanks also for introducing Leah Sutherland in to my podcast experience: she sounds like tons of fun!)

Now forgive me for bothering you with a question I’ve been carrying with me for quite some time, about the reconstruction of the faces of those ancient skulls, or any skull, really.

They look amazing -mostly-, and I understand it’s a real art... but is it science?

Has anyone ever reconstructed the face of someone whose countenance was known, but unknown to the artist doing the reconstruction? And, if so, how good a match was it?

Whenever I encounter such an reconstruction, I can’t help but wonder how helpful it is, in understanding who they were, how much they did or didn’t look like this elusive “us”.

How important do you think these faces are, and does seeing them help you in getting a feeling for how alike those ancient lives may have been?