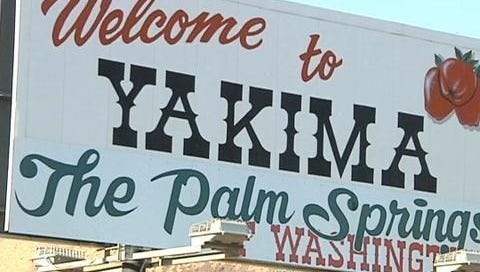

For the first eighteen years of my life, I lived in the very center of Washington state, in a city called Yakima. Shout-out to the self-proclaimed Palm Springs of Washington!

(Yes, that’s a real sign. It’s one of the few things outsiders tend to remember about Yakima, along with excellent cheeseburgers from Miner’s and one of the nation’s worst COVID-19 outbreaks.)

Yakima is a place I loved dearly and have returned to often over the years since, but I’ve never lived there again on a permanent basis. The same was true of most of my close classmates in high school: If they had left for college, most had never returned for longer than a few months at a time. Practically all of them now lived in major metro areas scattered across the country, not our hometown with its population of 90,000.

There were a lot of talented and interesting people in that group, most of whom I had more or less lost touch with over the intervening years. A few years ago, I had the idea of interviewing them to ask precisely why they haven’t come back and how they felt about it. That piece never really came together, but it was fascinating talking to a bunch of folks I hadn’t spoken to in years regarding what they thought and how they felt about home.

For the most part, their answers to my questions revolved around work. Few bore our hometown much, if any, ill will; they’d simply gone away to college, many had gone to graduate school after that, and the kinds of jobs they were now qualified for didn’t really exist in Yakima. Its economy revolved then, and revolves to an ever greater extent now, around commercial agriculture. There are other employers, but not much demand for highly educated professionals - which is generally what my high-achieving classmates became - relative to a larger city.

The careers they ended up pursuing, in corporate or management consulting, non-profits, finance, media, documentary filmmaking, and the like, exist to a much greater degree in major metropolitan areas. There are a few in Portland, and others in New York, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Austin, and me in Phoenix. A great many of my former classmates live in Seattle. We were lucky that one of the country’s most booming major metros, with the most highly educated Millennial population in the country, is 140 miles away from where we grew up on the other side of the Cascade Mountains: close in absolute terms, but a world away culturally, economically, and politically.

Only a few have returned to Yakima permanently after their time away. Those who have seem to like it well enough; for a person lucky and accomplished enough to get one of those reasonably affluent professional jobs, Yakima - like most cities in the US - isn’t a bad place to live. The professional-managerial class, and the older Millennials in the process of joining it, has a pretty excellent material standard of living regardless of precisely where they’re at.

But very few of my classmates really belonged to the area’s elite. It wasn’t a city of international oligarchs, but one dominated by its wealthy, largely agricultural property-owning class. They mostly owned, and still own, fruit companies: apples, cherries, peaches, and now hops and wine-grapes. The other large-scale industries in the region, particularly commercial construction, revolve at a fundamental level around agriculture: They pave the roads on which fruits and vegetables are transported to transshipment points, build the warehouses where the produce is stored, and so on.

Commercial agriculture is a lucrative industry, at least for those who own the orchards, cold storage units, processing facilities, and the large businesses that cater to them. They have a trusted and reasonably well-paid cadre of managers and specialists in law, finance, and the like - members of the educated professional-managerial class that my close classmates and I have joined - but the vast majority of their employees are lower-wage laborers. The owners are mostly white; the laborers are mostly Latino, a significant portion of them undocumented immigrants. Ownership of the real, core assets is where the region’s wealth comes from, and it doesn’t extend down the social hierarchy. Yet this bounty is enough to produce hilltop mansions, a few high-end restaurants, and a staggering array of expensive vacation homes in Hawaii, Palm Springs, and the San Juan Islands.

This class of people exists all over the United States, not just in Yakima. So do mid-sized metropolitan areas, the places where huge numbers of Americans live but which don’t figure prominently in the country’s popular imagination or its political narratives: San Luis Obispo, California; Odessa, Texas; Bloomington, Illinois; Medford, Oregon; Hilo, Hawaii; Dothan, Alabama; Green Bay, Wisconsin. (As an aside, part of the reason I loved Parks and Recreation was because it accurately portrayed life in a place like this: a city that wasn’t small, which served as the hub for a dispersed rural area, but which wasn’t tightly connected to a major metropolitan area.)

This kind of elite’s wealth derives not from their salary - this is what separates them from even extremely prosperous members of the professional-managerial class, like doctors and lawyers - but from their ownership of assets. Those assets vary depending on where in the country we’re talking about; they could be a bunch of McDonald’s franchises in Jackson, Mississippi, a beef-processing plant in Lubbock, Texas, a construction company in Billings, Montana, commercial properties in Portland, Maine, or a car dealership in western North Carolina. Even the less prosperous parts of the United States generate enough surplus to produce a class of wealthy people. Depending on the political culture and institutions of a locality or region, this elite class might wield more or less political power. In some places, they have an effective stranglehold over what gets done; in others, they’re important but not all-powerful.

Wherever they live, their wealth and connections make them influential forces within local society. In the aggregate, through their political donations and positions within their localities and regions, they wield a great deal of political influence. They’re the local gentry of the United States.

We’re not talking about international oligarchs; these folks’ wealth extends into the millions and tens of millions rather than the billions. There are, however, a lot more of them than the global elite that tends to get all of the attention. They’re not the face of instantly recognizable global brands or the subjects of award-winning New York Times profiles; they own warehouses and Applebee’s franchises, concrete companies and chains of movie theaters, hop fields and apartment complexes.

Because their wealth is rooted in the ownership of physical assets, they tend to be more rooted in their places of origin than the cosmopolitan professionals and entrepreneurs of the major metro areas. Mobility between major metros, the characteristic jumping from Seattle to Los Angeles to New York to Austin that’s possible for younger lawyers and creatives and tech folks, is foreign to them. They might really like heading to a vacation home in Bermuda or Maui. They might plan a relatively early retirement to a wealthy enclave in Palm Springs, Scottsdale, or central Florida. Ultimately, however, their money and importance comes from the businesses they own, and those belong in their localities.

Gentry classes are a common feature of a great many social-economic-political regimes throughout history. Pretty much anywhere you have a hierarchical form of social organization and property ownership, a gentry class of some kind emerges: the local civic elites of the Roman Empire, the landlords of later Han China, the numerous lower nobility of late medieval France, the thegns of Anglo-Saxon England, the Prussian Junkers, or the planter class of the antebellum South. The gentry are generally distinct from the highest levels of a regime’s political and economic elite: They’re usually not resident in the political center, they don’t hold major positions in the central administration of the state (whatever that might consist of) and aren’t counted among the wealthiest people in their polity. New national or imperial elites might emerge over time from a gentry class, even rulers - the boundaries between these groups can be more or less porous - but that’s not usually the case.

Gentry are, by definition, local elites. The extent to which they wield power in their localities, and how they do so, is dependent on the structure of their regime. In the early Roman Empire, for example, local civic elites were essential to the functioning of the state. They collected taxes in their home cities, administered justice, and competed with each other for local political offices and seats on the city councils. Their competition was a driving force behind the provision of benefits to the common folk in the form of festivals, games, public buildings, and more basic support, a practice called civic euergetism.

These local elites of the Roman world served as the linkage between the central administrative apparatus of the earlier emperors like Augustus or Hadrian and the archipelago of cities that made up the Roman Empire. This was how the Roman Empire could function with a central administration of only a few hundred scribes, clerks, and functionaries gathered around the emperor: The central state essentially outsourced the day-to-day running of the empire to the city councillors of Marseilles, Tarragona, Antioch, Athens, Carthage, and a hundred other cities scattered from Britain to Arabia. Places like this amphitheater in the southern Gallic city of Arles were the venues for, and expression of, what the Roman civic elite wanted to be seen doing:

(Note: the later Roman Empire, after the reforms of Diocletian, was a much different and dramatically more centralized entity, with a huge civil and military bureaucracy that reported directly to the emperor and his officials.)

Roman elites were fundamentally urban; they owned rural estates (fancy villas with vineyards and fields and bathhouses and libraries) and spent a great deal of time there, but cities were the venues for their competition with one another. The Roman Empire was an empire of cities, and those cities were the focal point of elite time and energy.

Now let’s contrast those Roman elites with the planter class of the antebellum South. Superficially, they share a great deal in common, and not just because the planter class loved to read the classics and explicitly model itself after the aristocracies of Greco-Roman Antiquity. Both were slaveholding elites, both valued a specific kind of elite education as a marker of social status, both owned extensive rural estates, and both exerted strong, effectively unchecked control over their localities. But the planter class was fundamentally rural; there were a few cities where they went to show off their wealth and sophistication, like Charleston, Augusta, and New Orleans, but by and large they spent their time and energy at their plantations. These were the places they effectively ruled, politicking with their fellow aristocrats and exerting effective control over their localities. There were incredibly wealthy planters with vast estates, some of them owning hundreds of enslaved people and thousands of acres, but plenty of planters operated on a more modest scale. But even the more modest planters - owning more than ten slaves in some areas of the South, more than twenty in others - were still an elite group by any reasonable standard.

The medieval European gentry was likewise a fundamentally rural group: living in their manor houses, collecting rents and customary labor duties from their serfs (or later in the Middle Ages, leaseholders), presiding over the local courts, and plotting and fighting with their gentry neighbors over inheritances, marriages, and access to the resources of whatever more centralized state existed. They were distinct from the higher nobility - dukes, counts, and whatnot - whose holdings included multiple estates and who were more directly connected to royal authority. Medieval Europe was notable for its general tolerance of private violence carried out not only by higher nobility but even local gentry, with their bands of men-at-arms and hired soldiers. That right to violence was part of what set them apart as a social group, and which they didn’t hesitate to employ in defense of their position in local society.

We could talk about many, many more types of gentry: the timar-holders of the Ottoman Empire in the 15th and 16th centuries, who received a rural estate in return for military service to the state, and carried out state legal functions and occasionally tax collection at a local level; some of, but not all, the holders of iqta (tax revenue units) in the Delhi Sultanate of the 14th century; the English country gentry of the 18th and 19th centuries; on and on and on. The greater the level of social inequality, the more prominent the gentry class - the group that owns the resources - tends to become in economic and political life. In agrarian societies, where land and its produce form the primary source of wealth, it’s rural elites who dominate. In more urbanized societies, the local elites can be a bit more diverse.

This, not just pure nostalgia, is why I started with Yakima: because it’s easy to see the structural parallels with the past when we look at a heavily rural and agricultural region, even one that’s not exactly prominent in the American imagination. The gentry residing in my hometown largely own land, the products of which form their primary source of wealth, and they sit atop the local hierarchy. But much of the United States isn’t as rural or as obviously hierarchical, in both social and racial terms, as Yakima. It’s not hard to spot vast apple orchards or sprawling vineyards and figure out that the person who owns them is probably wealthy; it’s harder to intuitively grasp that a single family might own seventeen McDonald’s franchises in eastern Tennessee, or the kind of riches the ownership of the third-biggest construction company in Bakersfield might generate.

When we talk about inequality, we skew our perspective by looking at the most visible manifestations: penthouses in New York, mansions in Beverly Hills, the excesses of hedge fund billionaires or a misbehaving celebrity. But that’s not who most of the United States’ wealthy elite really are. They own $2 million houses on golf courses outside Orlando and a condo in the Bahamas, not an architecturally designed oceanfront villa in Miami. It’s not that those billionaires and excesses don’t exist; it’s that they’re not nearly as common as a less exalted kind of wealth that’s no less structurally formative to our economy and society.

There are an enormous number of organizations and institutions dedicated to advancing the interests of this gentry class: Chambers of Commerce, exclusive country clubs and housing developments, the American Society of Concrete Contractors, and fruit-growers’ associations, just to name a small cross-section. Through these organizations and their intimate ties to local and state politics, the gentry class can and usually does wield significant power to shape society to their liking.

It’s easy to focus on the massive political spending of a Sheldon Adelson or Michael Bloomberg; it’s harder, but no less important, to imagine what kind of deals about water rights or local zoning ordinances are being struck across the country on the eighth green of the local country club.

For the uber-rich, thinking of dynasties comes naturally: wealth and privilege passed down from generation to generation, eccentric heirs and heiresses cultivating odd hobbies and occasionally stumbling into the presidency.

One of my all-time favorite pieces of writing, by the wonderful David Roth, is entitled “Bless This Oafish Koch Heir and His Hideous Shirts.” It’s about Wyatt Ingraham Koch, an impossibly wealthy son of one of the lesser-known Koch brothers, and his passion for absolutely godawful shirts.

I encourage you to read it, because it’s cutting and insightful and deeply hilarious, but for every Wyatt Ingraham Koch and his dumbass shirt company, there are a hundred equally loutish but far-less-exalted failsons of the American gentry running around.

Sure, some people work their way into this property-holding gentry class by virtue of their blood, sweat, and sheer gumption. That’s one variant on the American Dream: the belief that hard work and talent, and maybe a bit of luck, can take a person into the ranks of the elite. But far more of the gentry class are born into it. They inherit assets, whether those are car dealerships, apple orchards, or construction companies, and manage to avoid screwing things up. Managers run their companies, lawyers look over their contracts, accountants manage their finances, but they’re the owners, whether or not they’ve done a single thing of their own volition to accumulate those assets.

Gentry classes are generally hereditary. The one I’ve laid out in the United States certainly is, though it’s not entirely closed to new blood. Large amounts of property of any kind form a pretty durable base for generational wealth, whatever specific shape it might take.

Equating wealth, especially generational wealth, with virtue and ability is a deeply American pathology. This country loves to believe that people get what they deserve, despite the abundant evidence to the contrary. Nowhere is this more obviously untrue than with our gentry class. They stand at the apex of the social order throughout huge swathes of the country, and shape our economic and political world thanks to their resources and comparatively large numbers, yet they’re practically invisible in our popular understanding of these things.

Power resides in group photos of half-soused overweight men in ill-fitting polo shirts, in gated communities and local philanthropic boards. You’ll rarely, if ever, see these things on CNN or in the New York Times, but they’re no less essential to understanding how and why our society works the way it does.

This is an eloquent description of an influential but undercovered class in American society. My wife and I lived in Nashville for 6 years, and recently a number of America's worst humans (Art Laffer, Ben Shapiro, Tomi Lahren) have moved there. Though the superficial appeal is obvious, as it's in the South and leans into country aesthetic, like many large metros is full of progressives, more so than other red state metros of comparable size, such as Jacksonville or OKC. It's not clear why, if one's stated reason to leave California for a conservative area, one would choose to live in Nashville.

A component of the appeal may be that "gentry" are relatively dominant in Nashville local politics. Lee Beaman, a four-times divorced car dealership owner essentially killed two pieces of transit legislation in the six years I lived there through personal lobbying (albeit with an assist from Koch brothers money). Steve Smith, who owns the most honky tonks downtown routinely flaunts local regulations, including by keeping his bars open and packed during the pandemic. He got away with it for months, and the mayor of Nashville ended up doing his PR dirty work by covering up evidence that Smith's honky tonks contributed to COVID-19 spread.

The significant power that gentry amass can challenge or even exceed that held by local democratic institutions, particularly when said institutions are hollowed out by decades of low tax revenue and public delegitimization. This is a fundamental component of what conservatives envision when they advocate for enabling local institutions to manage their own affairs. They're not transitioning power from the federal government to city halls, but from the federal government to local jetski magnates.

Hello, I thought this was a nice bit of writing. Just wanted to chime in here because I don't think it was mentioned in your post, but an astoundingly high percentage of these "local gentry" types are owners of car dealerships. These businesses - geographically protected by laws that prohibit selling cars on the internet, etc. - form a sort of American archipelago of private wealth, the "big men" of their particular communities. I've long thought that so many of our difficulties in building green infrastructure, reducing fossil fuel dependence, properly funding and building transit, and mitigating climate change are from precisely this organized cabal of auto dealership owners. That is, the immovability of American car culture may be less about GM/Ford than the local Chevy dealer. Worth exploring. Cheers.