By the time innovative foragers along the Yangzi and Yellow Rivers began experimenting with planting rice and millet more than 10,000 years ago, transforming the region into one of the world’s original agricultural heartlands, people had already been living in East Asia for a very long time. Homo erectus and perhaps even its more ancient predecessors had made what’s now China their home since at least 1.66 million years ago; in fact, Homo erectus in the strictest sense is a species found mostly in East Asia.

The probable descendants of Homo erectus, Denisovans, were likely widespread in the region. Even though Denisovan fossils were first found in what’s today western Siberia, at the eponymous Denisova Cave, a jawbone found in Tibet was recently confirmed to be Denisovan on the basis of proteomic analysis:

If they were living in Tibet and Siberia, Denisovans were almost certainly living in the more hospitable and accessible parts of East Asia as well. Present-day China and its environs are an excellent candidate for at least one of the known interbreeding events between Denisovans and anatomically modern humans. Tianyuan Man, found in a cave near Beijing and dating to more than 40,000 years ago, already had Denisovan admixture; so did his successors, who spread throughout East Asia by several different routes between then and the Last Glacial Maximum around 20,000 years ago.

As the glaciers began to recede from their greatest extent, East Asia looked very different than it does today:

![Coastlines of the Ice Age - East Asia [5900x4666] [OC] : MapPorn Coastlines of the Ice Age - East Asia [5900x4666] [OC] : MapPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!myHZ!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F3feeb221-0fbe-48fa-a9e7-4afff7a49bc7_253x200.jpeg)

Sea levels were so much lower that the Korean peninsula wasn’t a peninsula; the Yellow Sea, to its west, was a wide, low-lying, grassy plain. The islands of Japan formed a single landmass, connected to the mainland in the north via what’s now Sakhalin Island, and only a narrow channel separated it from Korea. The Sea of Japan was in fact practically an inland sea. Taiwan was likewise part of the mainland.

Environments were different, too. It was colder and drier (10-15 degrees Fahrenheit colder in northern China), as it was across most of the world, and grasslands predominated. In those conditions, the people who lived in East Asia weren’t dramatically different than their contemporaries elsewhere on the planet. They followed the big game as it migrated seasonally across the landscape, moving frequently from place to place in small bands. Their subsistence strategy was extensive, meaning they focused on high-value resources, like aurochs or mammoth or rhinoceros, that were spread thinly across the landscape. Basically, they moved a lot to get the food they preferred.

But as the glaciers melted and the seas rose, as it got warmer and wetter and generally more hospitable, the environment changed. Forests replaced the open grasslands. The big grazers, like mammoth, bison, and rhinoceros, either went elsewhere or died out. This meant that people had to shift their ways of living if they wanted to stick around. It’s not that the emerging landscapes were less productive or welcoming to people; they were simply different, with different potential food sources that required different strategies to acquire and utilize them.

Some of those shifts were straightforward. Deer and boar loved the new forests, and while the strategies for hunting them were much different than what people had done to take mammoth or bison or caribou, the game was plentiful. The residents of East Asia had always hunted this smaller game in addition to the bigger prey; now it was the focus, along with panda, tortoise, and even smaller animals.

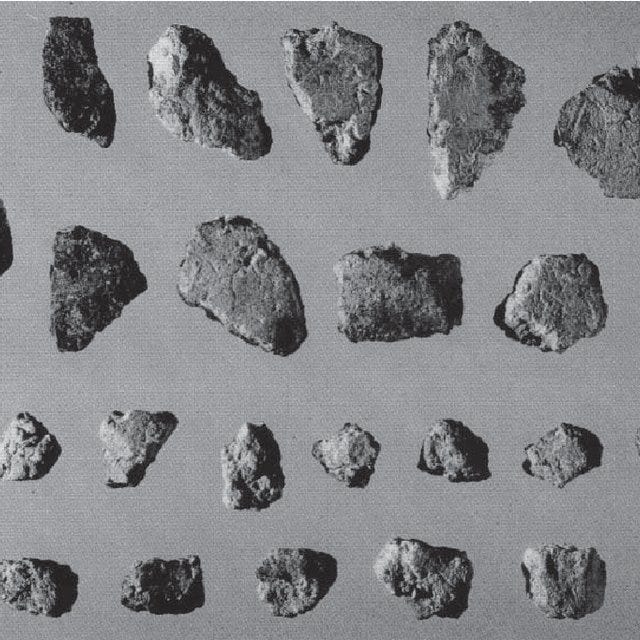

Other changes, however, were more complex. The new forests were chock-full of nut-bearing trees: chestnuts, acorns, and so on. Nuts could be a fantastic source of food that lasted for years if properly stored, and some could be eaten right off the tree, but others required more work to be made edible. Some of them were loaded with toxic tannins that had to be removed prior to eating. People had to leach horse chestnuts in cold water and use a combination of heating and lye to make deciduous acorns safe to eat. Even after that, they still had to be ground up into a flour or paste, then baked or cooked into some kind of gruel. That need for cooking was probably the context that produced the world’s oldest pottery, like these ceramic sherds more than 16,000 years old from the Odai Yamamoto I site in Japan:

These crumbly fragments don’t look like much, but pottery was a big deal. It appeared a bit earlier along the Amur River of eastern Siberia, then a little bit later at various places in China. Pottery made cooking dramatically easier, and opened up a variety of new possibilities for storage and food preparation.

The same was true of grasses, like rice and millet. They were often plentiful, with huge stands of the stuff just sitting there, but it took a lot of work to turn stalks of grass into something worth eating. As the climate shifted, the grasses and nuts started to look a lot more attractive to the residents of East Asia. They developed new technologies to make use of them, like grindstones, sickles, and better pottery, like this jar from Shangshan along the lower Yangzi River, dating to around 9,000 years ago:

All across East Asia, people were trying out what’s called an intensive or broad-spectrum subsistence strategy. This involved a wider range of food sources and less movement, using a more specialized set of technologies and tools. Nuts were popular everywhere, but especially in Japan, where the Jomon people extensively modified the landscape to produce more of their favored nut-bearing trees. The Jomon were so successful with this strategy that their numbers grew dramatically, and they became some of the first people in the world to settle down in what we can call “villages.” They lived in semi-subterranean houses like these reconstructions at the Uenohara site in southern Kyushu:

These little huts look humble enough, but they were a significant investment of time and energy. The reconstructions don’t show purpose-built flues or the stone-lined hearths the Jomon constructed outside their dwellings. Those improvements were essential for long-term food preparation and storage. Instead of moving with the food, the Jomon were settling down in a single spot for most of, or even the entire, year. They made use of all the available foods in their area; the Jomon were particularly fond of combining nut-flour with boar or deer meat, blood, and bird-eggs, making a sort of hamburger/pancake. Clever.

The Jomon weren’t unique in this regard. All across East Asia between about 8,000 and 10,000 years ago, people were trying out similar innovations: grindstones, food storage and preparation, pottery, intensive subsistence strategies, and a sedentary lifestyle. The precise nature of their food resources varied - some people fished more, others ate more snails or taro root, wild millet or rice - but the broad patterns were similar.

Before long, though, some people took these innovations further. Wild grasses are great, but why not try planting some? If you like those particular chestnut trees more than others, why not plant those nuts and see if they’ll grow in that nice spot over there? Pigs are tasty; why not see if we can keep some of them around permanently? Along the Yangzi and Yellow Rivers, experiments in sedentism and cultivation began to take on a more transformative cast. The Neolithic, which would provide the ancestors of the foods that feed billions of people today, would soon be underway.

If you’ve enjoyed this, check out today’s episode of Tides of History on the deep prehistory of East Asia.

It's always interesting to learn about East Asian history. We never learn enough of it in the Western world.

Very interesting!!! Thanks! 👍